The Accountability Gap: Who’s Responsible for Responsible AI?

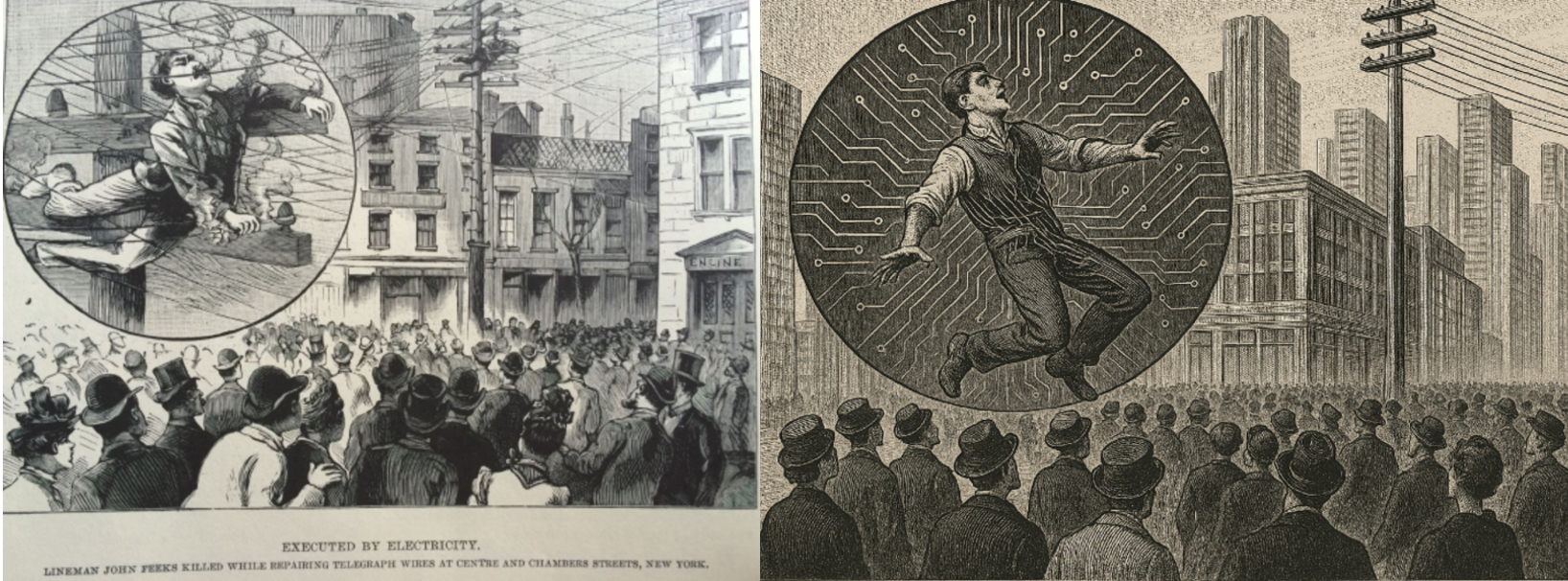

When electricity first began to power cities in the late nineteenth century, technological progress moved faster than regulation. Thomas Edison and George Westinghouse were engaged in what became known as the War of Currents, each arguing for the safety of their own system while resisting external oversight.

Edison believed that excessive attention to safety and regulation could slow public adoption, and that too much caution might hold back the use of electricity in general. The War of Currents finds a modern parallel in a war of context: where electricity once powered cities, language now powers decisions, and questions of accountability remain unresolved.

AI today occupies a comparable stage of development. The technology is advancing at great speed, but the risks are increasingly evident: impacts on mental health, erosion of public trust, and the spread of unregulated or unsafe information. As systems grow more capable, the question of who bears responsibility for their behaviour grows more complex.

The Key Players

- The Labs

Model creators such as OpenAI, Anthropic, and Google DeepMind occupy a foundational position in the AI ecosystem. They design, train, and calibrate large-scale systems whose influence extends far beyond their own infrastructures. Yet their formal responsibility typically ends with the publication of a model card or a safety statement.

While leading labs have invested heavily in alignment research, red-teaming, and safety evaluations, these remain largely self-regulated processes. Independent scrutiny is limited, and transparency is often constrained by competitive and commercial pressures. Once released, models become substrates for thousands of downstream uses that may diverge substantially from their original intent.

- The Deployers

Organisations integrating AI into their products or workflows bear the most visible operational risks. These actors face the reputational and legal consequences when models behave unpredictably or harm users.

However, many deployers lack meaningful visibility into the systems they use. Access to training data, model weights, or internal safeguards is often restricted by providers, creating a governance asymmetry: accountability without insight.

The EU AI Act attempts to address this by making deployers responsible for ensuring “appropriate testing and risk management” prior to release, even when they did not develop the underlying model. Yet without tools or standards for independent testing, compliance risks becoming procedural rather than substantive.

- The Developers

Software engineers, prompt designers, and data scientists sit at the interface between innovation and implementation. They are typically the first to observe safety risks, such as bias in outputs, inconsistent performance, or unintended behaviours, but they often lack institutional authority or resourcing to address them.

Scaling responsible AI practices within engineering teams requires more than technical guidance; it demands organisational commitment. In practice, developers are frequently constrained by commercial timelines and product pressures. The prevailing culture of “move fast, fix later” leaves safety as an afterthought rather than a design principle.

- The Regulators

Governments and standards bodies are now racing to keep pace. The establishment of the UK AI Safety Institute, the EU AI Office, and the US NIST AI Safety Institute represents a growing recognition that AI oversight must be institutionalised.

Yet enforcement remains fragmented. Regulatory bodies are under-resourced, and international coordination is still emerging. The global nature of AI development complicates jurisdictional authority: a model trained in one country can be fine-tuned, deployed, and cause harm in another.

As a result, current frameworks tend to focus on documentation and risk classification rather than empirical testing. The shift from guidance to verification, and from principle to practice, is still underway.

- The Public

End-users experience the outcomes of AI systems most directly. They encounter biased recommendations, misleading information, and interactions that can affect mental health, financial stability, or civic trust. Yet they possess limited transparency into how these systems operate or who can be held accountable when harm occurs.

But the public is not only affected by AI, it also shapes its trajectory. Responsible use depends on informed engagement: understanding the capabilities and limits of these systems, questioning their authority, and recognising when automation should be challenged.

Building this awareness requires education, transparency, and open dialogue. Without it, meaningful consent or redress remains nearly impossible, and the gap between developers and society only widens.

Responsible AI begins with responsible testing.

In this fragmented landscape, independent evaluation remains one of the few concrete mechanisms for accountability.

External testing brings transparency, documentation, and empirical evidence—demonstrating that an organisation has taken safety seriously before deployment. Independent red-teaming and safety auditing turn accountability from a principle into a measurable practice.

Until regulation and governance mature, such evaluation offers the clearest signal of responsibility.

At SenSafe AI, we focus on providing transparent, repeatable safety testing, helping organisations understand, document, and improve the reliability of their models before they reach users.

Get in touch. We'd love to discuss how our reports can help your organisation bridge the accountability gap.